This Shabbat we finish reading the Book of Exodus.

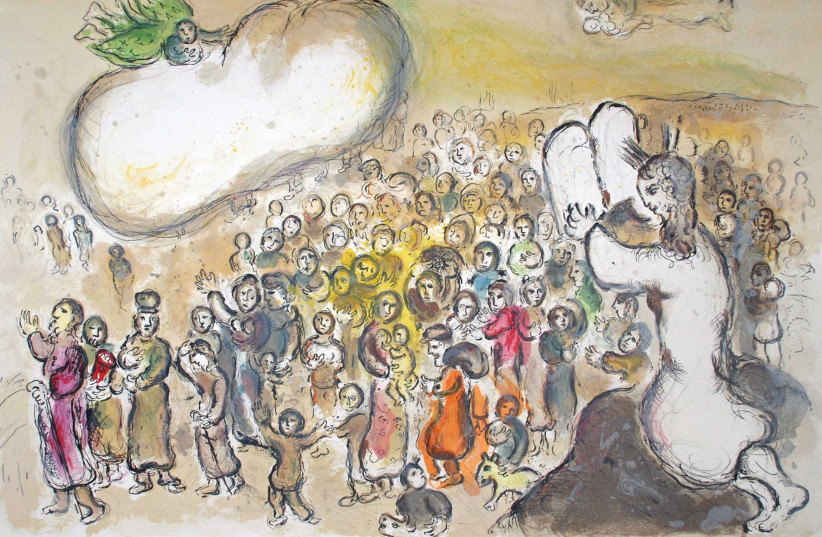

It tells the story of a people who went down to Egypt as free individuals, who became enslaved and lost almost all traces of their identity. They were finally delivered by the strong arm of God from the bonds of Egyptian slavery in order to begin the arduous process of becoming the nation of Israel, discovering the complexities of freedom and the consequences of free will alongside the growing knowledge of God via Divine revelation.

I have always found much of the end of Exodus tedious, centered as it is on the endless details of instruction for building the Tabernacle and weaving the priests’ garments. The last six chapters repeat almost verbatim the same details when describing constructing the actual Tabernacle.

It was thus my great fortune to discover a beautiful reading of Exodus by Leon Kass in his book Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus, which has transformed the entire biblical book for me, particularly its end.

One of the ideas he develops is that, at God’s initiative, the people become co-partners of God in the venture of building their nationhood, with God at its center.

Nowhere is this more palpable than in the creation of the Tabernacle, which God designs but the people actually construct.

This unique building project reflects the tremendous intimacy latent in the relationship between Israel and God, which is often compared to a bride and groom, with Sinai representing the wedding canopy. After a wedding, a couple naturally must find a space in which to build a home. So, too, with God and Israel.

Unlike the creation of the world, in which God is the sole Creator, here the people, who were created in the image of God, are commanded to create the space for God to dwell among them. The chief architect’s name, Bezalel, carries within it “btzelem elokim” – meaning “in the image of God” – as central to identifying the core quality of the person who will oversee the translation of God’s word into the construction of an actual physical space that will house both the human and the Divine.

WHAT MAKES the relationship even more remarkable is what happens in the aftermath of the sin of the golden calf. Many commentaries recognize that the story of the golden calf creates a separation between the command to build the Tabernacle and its actual building, reflecting the schism caused by the terrible betrayal of God by His newly formed nation. The repetition of the information can be seen on a profound level as an act of rebuilding and renewing the commitment to the relationship between God and Israel.

Nothing will ever be as it was, but the story teaches us that there can still be intimacy deepened by the acute awareness of fragility, remembered pain of betrayal, and a core strength that comes with resilience infused by the effort of winning forgiveness.

It seems to me that the golden calf becomes a catalyst for tremendous growth and maturity, as only by disobeying are the former slaves able to understand the consequences of free will.

In the aftermath of this sin, there is remarkable softening and increased intimacy between God and Moses, as God reveals more and more of Himself, culminating in the 13 attributes, which teach Moses about Divine compassion and forgiveness along with an actual glimpse of the Divine, which will forever after be reflected on the face of Moses.

In addition, there is incredible closeness that emerges between Moses and the people as he becomes the leader he was meant to be, fully present and aware of the people’s shortcomings but choosing to continuously champion them throughout his encounters with the Divine.

The two Tabernacle sections in Exodus present a model for what a relationship looks like before and after a terrible rupture. Things may not be the same as before, but relationships can be repaired and rebuilt.

Kass writes at the end of his book, “As a cooperative project between Creature and Creator, the Tabernacle stands as a completion of the Creation – not as a summary or microcosm, but as the culmination. God’s creation produced a hospitable world in which human beings can live. God’s law sets forth a Way under which they can live well. God’s Tabernacle, built for Him by human beings, offers rituals by which they can aspire to be holy, as the Lord their God is holy.”

There is a midrash in Leviticus Rabbah that daringly suggests that when God asks us to take a teruma or offering, He is really asking that we should take Him as the offering. In other words, God ardently desires to be invited into the sacred spaces that we create. We are all Bezalel, and we have both the individual and collective mandates to actively initiate the following of God’s law so that we can experience our own encounter with the Divine both within ourselves and rippling outward to those who live among us.

AS I sit to write this column, it is hard to ignore the difficult pictures and stories coming out of the Ukraine. I am understandably moved by the stories of rabbis and their wives who are choosing to stay with their vulnerable populations of orphaned children, elderly and sick men and women despite the unthinkable conditions and dangers that they are facing.

Their sacred work is an inspiration and continuously invites the Divine presence into the world. This column is dedicated in their honor. ■

The writer teaches contemporary Halacha at the Matan Advanced Talmud Institute. She also teaches Talmud at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies along with courses on sexuality and sanctity in the Jewish tradition.